The Gwrando programme was created as part of the United Nations Decade of Indigenous Languages and to allow artists to listen and learn from the many endangered Indigenous languages of the world. Here is Chembo Liandisha talking about their project and journey so far.

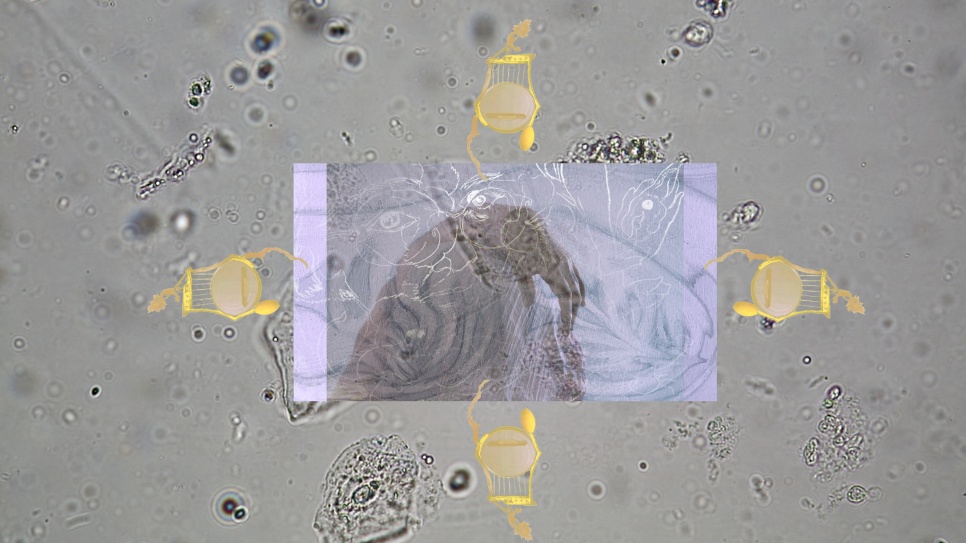

Namwva is an audio/visual project that investigates the difficulties in adjusting to the ever changing environmental and social landscape of Katete via listening to the concerns and hopes of the Chewa elders and youth from the area and Lusaka, Zambia.

Which Indigenous language / community have you been listening to and who have you been collaborating with?

The Chichewa / Achewa term Namwva itself loosely translates into English as “I have heard/ I have listened”. I began the process of listening by using online platforms to connect with young Chewa people most who live in Lusaka, Zambia. Sharing my personal issues with my tribal identity led to us discussing Chewa identity, the preservation, use of and prevalence of the Chewa language, the protection of the environment in the Chewa homeland, Katete and many more things. My partner organisation in Zambia was Circus Zambia.

What would you like to share about your journey?

When I visited Zambia, most of the young people of Chewa lineage in Lusaka openly expressed fears that the language is dying citing pressures stemming from English being Zambia’s official language. This proves to be a problem as people are forced into choosing to be fluent in English above their own due to its commercial, professional and societal value.

When I travelled to Katete with my colleague from my Circus Zambia we met with an elder from the village who told us that meeting the Gawa Undi Paramount Chief/King of the Chewa of Zambia, was a very serious and delicate process. We were told that it was impossible for us to expect to be in his presence within a day or two of engaging with the elders. From this interaction it was obvious that we would have benefited from making contact with an elder a month or so in advance, as a sign of respect and reverence to the Chief. This process taught me that patience and research are key in the process of listening.

What are your aspirations for the UN Decade of Indigenous Languages?

To me, the UN decade of languages is a chance for people of the world to deepen their connection to their mother tongue as well as the languages of the world that they have always desired to connect with.

This is not a chance to simply document and analyse the current ability of these Indigenous and endangered languages but also a chance to deepen the knowledge base of each language system to preserve it for the future.

My personal hopes are to further my rooting in my own mother tongue by using this decade to elevate the perspective on these languages as well as the cultures they come from. I hope my contribution will be reflected in the mindsets of young and contemporary Zambians (not only limited to the Achewa tribe) I am very hopeful that we will revive our currently dying languages during this decade across the world and further strengthen the cultures and people they come from.

What’s one practical lesson you’ve learnt and would like to share with other artists about working with Indigenous languages?

In conclusion, my advice to artists or people who wish to work within the Indigenous community or language space is to always respect the people you desire to listen to or learn from. This can look like staying silent and allowing people to process your questions, refraining from asking further questions when there are visual cues that the “subject” is uncomfortable or no longer wishes to share. We need to learn to hold space for the emotional journey they may be on due to notions which can be challenging.

Here is a short film produced about the journey. This film is currently a work in progress.